Falling ill is always a bummer. It’s even more annoying when you just finished preparing a poster for a conference you intended to attend (in the current case this is the annual IAP meeting). Per doctor’s orders I am not allowed to be patient zero at the above conference, so my poster will end up alone at the site (luckily my nice colleagues will take it along and put it up). Because misery loves company (or it’s just a personal skill to pick the wrong moment) I had also decided to make this poster a bit more interactive through a spartan setup: As little text as possible, only a trail of images through which I would tell the story of the research…As you can see I was asking for trouble.

Not being able to be there physically, and knowing that most people nowadays own a smart-phone, I came up with the following solution: One of my colleagues will also put up a QR-code, sending the interested reader to this blog-post, where he/she will be able to read the story of the poster. (Questions can be put in the comments, and the full size version of the poster can be reached by clicking on the picture below.)

Abstract

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) are a versatile class of crystalline materials showing great promise in a wide range of applications. Recently, light-based applications, with a focus on luminescence and photo-catalysis, have become of interest. Although new luminescent MOFs are readily synthesized, a fundamental understanding of the underlying mechanisms in the electronic structure is often lacking.

First principles, or ab initio simulations of these MOFs can be used both for validating the experimentally proposed atomistic model of the MOF and for elucidating its luminescent behavior. On this poster, two different MOF-topologies are investigated. In the first case, we consider the well-known UiO-66(Zr) MOF. For this MOF, it is known that functionalization of the linkers modifies its luminescent behavior. As our second case, we consider the very recently created/synthesized COK-69(Ti) MOF. This new MOF is both flexible and luminescent, making it of interest for various applications.

The Old: UiO-66(Zr)-X

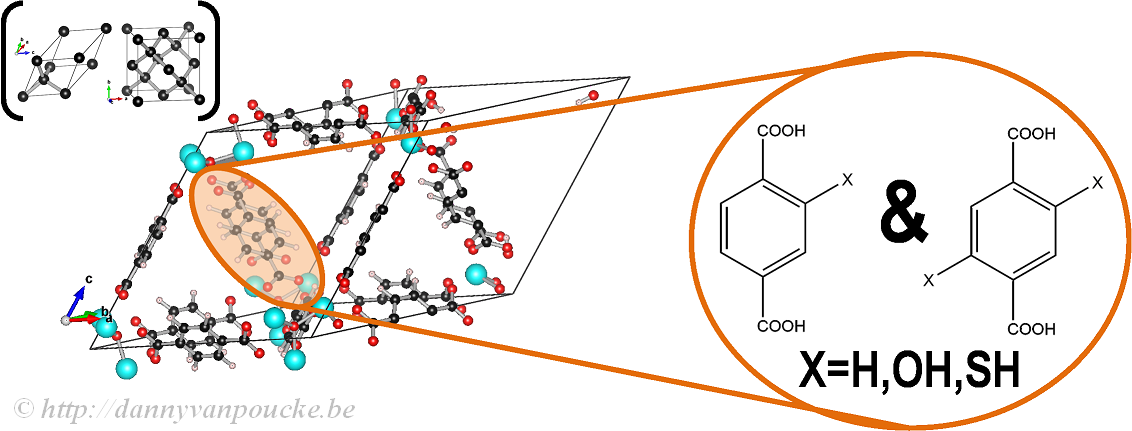

Atomic Structure

In our work on the UiO-66, we made use of the primitive unit cell, which contains only a single node and six linker molecules. This cell still contains about 120 atoms (in contrast to about 480 atoms for the conventional cubic cell) making it a rather large system from the point of view of ab initio calculations. The relation between this primitive unit cell and the conventional cubic cell is indicated by comparison to the diamond primitive and cubic cell (top left corner).

The functionalized versions of this MOF were created by manually replacing some of the H atoms of the BDC-linker (benzene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid) by the functional group of interest (OH or SH) and then optimizing the entire structure.

Ball-and-stick model of a primitive unit cell of UiO-66(Zr). Linker functionalization is indicated on the right. Primitive and conventional unit cells for diamond are given as reference.

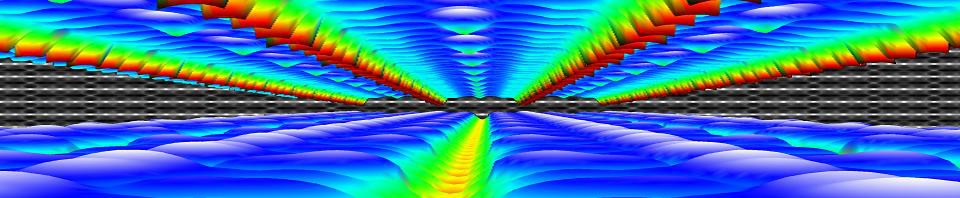

Electronic Structure

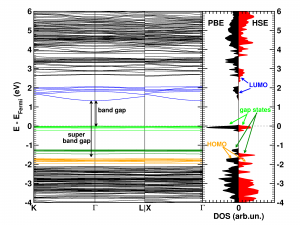

The calculated electronic band structure (left) and density of states (right) of the double SH-functionalized UiO-66(Zr). The conduction band is colored in blue, while the gap states related to the functional groups are colored green. The “old” valence band is colored yellow. This picture is a modified version of the published one.(Ref 1)

Starting from the optimized geometrical structures, the electronic structure is investigated. Taking three high-symmetry lines of the first Brillouin zone, the band structure was generated for all the functionalized MOFs.

The first aspect that drew my attention was the fact that the bottom conduction bands (indicated in blue) remained unchanged while part of the top of the valence band (indicated in green) splits off and moved upward into the band gap. At this point, nomenclature also becomes a bit of a problem. In a doped semi-conductor, the green bands would be called gap states, which would mean that the band gap of the host-material remains unchanged (which is actually also the case here, the distance between the yellow valence band and the blue conduction band is exactly the same for all functionalized UiO-66(Zr) systems we investigated). However, unlike those semiconductors, these gap states are entirely filled, and contain a significant electron occupation (in doped semi-conductors, these states often appear due to ppm doping). Because of this, they take the role of the valence band leading to a measured band gap equal to the distance between the top green bands and the conduction band (blue). So we end up with two band gaps. To have a clear link with experiments on MOFs, we will call the latter the band gap, while we will call the distance between the yellow and blue bands the “super band gap” (super, to indicate that we go beyond the size of the band gap, but it can still be considered a band gap. If that were not the case, we should call it the “supra band gap”).

The discussion of the super band gap can be rather short: it remains unchanged from the value of the unfunctionalized UiO-66(Zr): roughly 4 eV. In contrast, the band gap depends on both the functional group, and the number of functional groups present on each linker. In case of the double SH-functionalized linkers, each functional group leads to a gap state that is being split of from the valence band (cf. two green bands in the right picture).

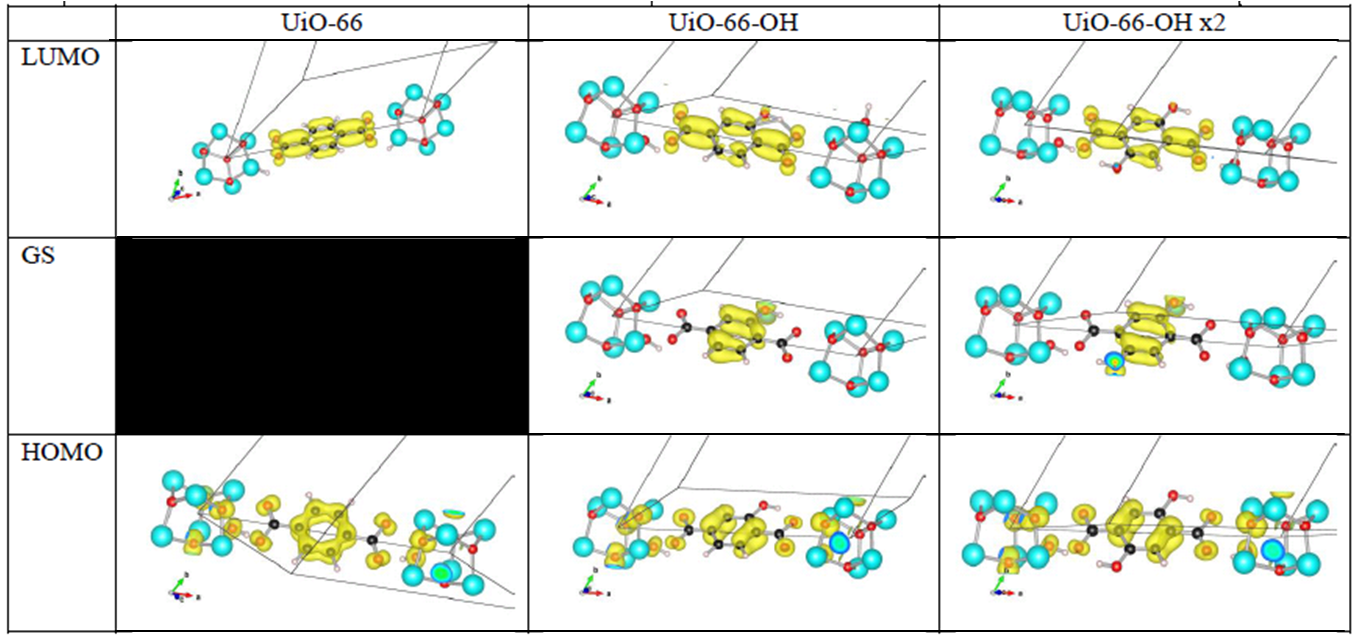

Orbital character of gap states, and valence and conduction bands for OH functionalized linkers in UiO-66(Zr).

Analysis of the orbital character shows that the splitting of the valence band can be taken quite literal. Where the valence band (or HOMO if you use molecular terminology) of the unfunctionalized UiO-66(Zr) mainly consists of the π-orbital of the BDC linker, this orbital is split upon functionalization. The conduction band orbital (or LUMO) on the other hand is barely modified.

Because LDA and GGA functionals are well-known to underestimate the experimental band gaps (even though the band structure is qualitatively well represented), we have also used a hybrid functional (HSE06, which was developed for solids) to calculate the band gap, and as expected, we find that the qualitative picture of the electron density of states (DOS) is retained, and the resulting calculated band gap is in perfect agreement with the experimentally measured values (experiments performed by Kevin Hendrickx of the Centre for Ordered Materials, Organometallics and Catalysis at Ghent University).

In conclusion, our ab initio calculations have shown us that functionalization of the linkers leads to a splitting of the valence band and the creation of a gap state, and that the band gap can be predicted with great accuracy for these materials.

The New: COK-69(Ti)

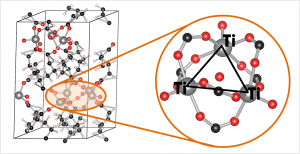

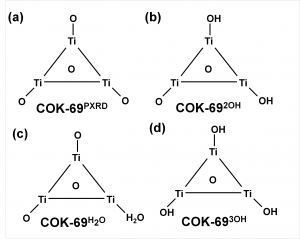

Atomic Structure

The COK-69(Ti) MOF is a newly developed MOF by the Center for Surface Chemistry and Catalysis of the university of Leuven. It is one of the few Ti containing MOFs that have already been synthesized. Because of this, the initial model provided was not sufficiently accurate to perform good electronic structure calculations. The weak point of the model was the uncertainty of the actual structure of the triangular Ti-O clusters. The original model (figure a) was not charge balanced. As a result, the electronic structure of this model showed it to be a metal (or a very narrow band gap semiconductor), in clear disagreement with experiment. Charge balance could be obtained in several ways: removal of O atoms, formation of H2O bound to the cluster (e.g. figure c) or the formation of OH groups (e.g. figure b). By investigating different models, we found that the removal of O atoms is highly unfavorable, while the formation of OH groups and a bound H2O molecule are comparable in stability. As a result of the latter observation, it is not unreasonable to assume that under experimental conditions the bound H2O molecule dissociates and lead to the formation of two OH groups, and that this process is also reversed, leading to a constant moving back and forth between the two models.

Electronic Structure

Also, the calculated electronic structure for both models is reasonably comparable: similar sized band gaps, and the same character for the valence (mainly O states) and the conduction (mainly Ti states) bands. Making it hard to give preference to one model over the other as being the actual ground state structure of this MOF, without further study.

Irradiated COK-69

More interestingly, we found the cluster with three OH groups (cf. figure d) to be most stable. In such a model, two of the Ti atoms should have an oxidation number of 4, while one has an oxidation number of 3. Looking into the electronic structure of this specific model of the COK-69 shows some amazing features. Firstly, the band gap is much reduced to about the size associated with a semiconductor, and secondly, the states of the Ti3+ atom show a valence to conduction transition of 3.2 eV, which roughly coincides with the blue color obtained for the irradiated COK-69 MOF.

Two samples of the COK-69(Ti) MOF. The normal COK-69 at the top, and the irradiated COK-69 MOF at the bottom. Figure taken from Ref 2.

Ti3+ centers are known to provide a blue color in other materials, and it is now also shown to be the case for this MOF. In addition, experiments on the irradiated COK-69 MOF also showed that no more than 1/3 of the Ti atoms could be Ti3+, which is also the maximum indicated by our model (one Ti per Ti-cluster).

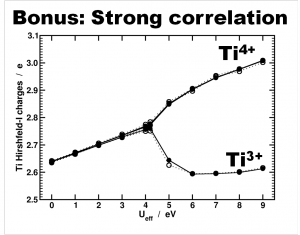

Another interesting bonus provided by this last model is from the theoretical perspective. Due to the symmetry of the cluster and the strong correlation of the Ti-d states, standard DFT is not able to differentiate between the Ti4+ and Ti3+ atoms. As such, the atomic charge is the same for all. By adding an additional Hubbard U potential on the Ti-d states (the so-called DFT+U approach) it is possible to differentiate between the different Ti oxidation states, as is shown by the nice bifurcation diagram.

Differentiation of Ti species as function of the U value used in a DFT+U approach. Atomic charges are calculated using the Hirshfeld-I partitioning scheme[3]. Figure taken from Ref 2.

In conclusion, our ab initio calculations allowed us to build a more accurate model of the COK-69 MOF and provide a model for the irradiated COK-69 MOF. In case of the latter, the calculated electronic structure can be used to elucidate the blue color of the irradiated COK-69.

References

[1] “Understanding intrinsic light absorption properties of UiO-66 frameworks”, K. Hendrickx, D.E.P. Vanpoucke, K. Leus, et al. Inorganic Chemistry (in revision)

[2] “A Flexible Photoactive Titanium MOF based on a [TiIV3(µ3-O)O2(COO)6]-Cluster”, B. Beuken, F. Vermoortele, D.E.P. Vanpoucke, et al. Angewandte Chemie (accepted)

[3] D.E.P. Vanpoucke, P. Bultinck, and I. Van Driessche, J. Comput. Chem. 34 405-417 (2013) & J. Comput. Chem. 34 422-427 (2013)