Today we had our fourth consortium meeting for the DigiLignin project. Things are moving along nicely, with a clear experimental database almost done by VITO, the Machine Learning model taking shape at UMaastricht, and quantum mechanical modeling providing some first insights.

Tag: computational materials science

Permanent link to this article: https://dannyvanpoucke.be/digilignin-c4-en/

Mar 06 2024

First-principles investigation of hydrogen-related reactions on (100)–(2×1)∶H diamond surfaces

| Authors: | Emerick Y. Guillaum, Danny E. P. Vanpoucke, Rozita Rouzbahani, Luna Pratali Maffei, Matteo Pelucchi, Yoann Olivier, Luc Henrard, & Ken Haenen |

| Journal: | Carbon 222, 118949 (2024) |

| doi: | 10.1016/j.carbon.2024.118949 |

| IF(2022): | 10.9 |

| export: | bibtex |

| pdf: | <Carbon> |

|

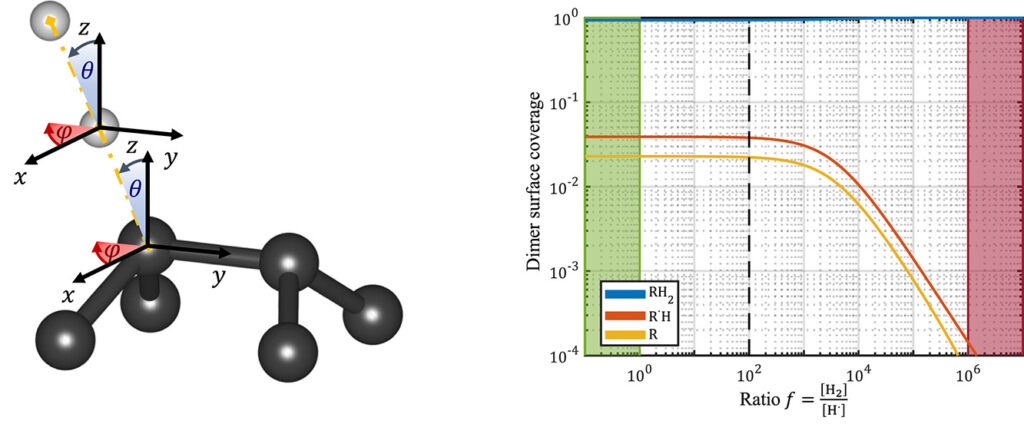

| Graphical Abstract: (left) Ball-and-stick representation of aH adsorption/desorption reaction mediated through a H radical. (right) Monte Carlo estimates of the H coverage of the diamond surface at different temperatures based on quantum mechanically determined reaction barriers and reaction rates. |

Abstract

Hydrogen radical attacks and subsequent hydrogen migrations are considered to play an important role in the atomic-scale mechanisms of diamond chemical vapour deposition growth. We perform a comprehensive analysis of the reactions involving H-radical and vacancies on H-passivated diamond surfaces exposed to hydrogen radical-rich atmosphere. By means of first principles calculations—density functional theory and climbing image nudged elastic band method—transition states related to these mechanisms are identified and characterised. In addition, accurate reaction rates are computed using variational transition state theory. Together, these methods provide—for a broad range of temperatures and hydrogen radical concentrations—a picture of the relative likelihood of the migration or radical attack processes, along with a statistical description of the hydrogen coverage fraction of the (100) H-passivated surface, refining earlier results via a more thorough analysis of the processes at stake. Additionally, the migration of H-vacancy is shown to be anisotropic, and occurring preferentially across the dimer rows of the reconstructed surface. The approach used in this work can be generalised to other crystallographic orientations of diamond surfaces or other semiconductors.

Permanent link to this article: https://dannyvanpoucke.be/2024-paper-hadsorption-emerick-en/

Dec 13 2023

How to verify the precision of density-functional-theory implementations via reproducible and universal workflows

| Authors: | Emanuele Bosoni, Louis Beal, Marnik Bercx, Peter Blaha, Stefan Blügel, Jens Bröder, Martin Callsen, Stefaan Cottenier, Augustin Degomme, Vladimir Dikan, Kristjan Eimre, Espen Flage-Larsen, Marco Fornari, Alberto Garcia, Luigi Genovese, Matteo Giantomassi, Sebastiaan P. Huber, Henning Janssen, Georg Kastlunger, Matthias Krack, Georg Kresse, Thomas D. Kühne, Kurt Lejaeghere, Georg K. H. Madsen, Martijn Marsman, Nicola Marzari, Gregor Michalicek, Hossein Mirhosseini, Tiziano M. A. Müller, Guido Petretto, Chris J. Pickard, Samuel Poncé, Gian-Marco Rignanese, Oleg Rubel, Thomas Ruh, Michael Sluydts, Danny E.P. Vanpoucke, Sudarshan Vijay, Michael Wolloch, Daniel Wortmann, Aliaksandr V. Yakutovich, Jusong Yu, Austin Zadoks, Bonan Zhu, and Giovanni Pizzi |

| Journal: | Nature Reviews Physics 6(1), 45-58 (2024) |

| doi: | 10.1038/s42254-023-00655-3 |

| IF(2021): | 36.273 |

| export: | bibtex |

| pdf: | <NatRevPhys> <ArXiv:2305.17274> |

|

| Graphical Abstract: “We hope our dataset will be a reference for the field for years to come,” says Giovanni Pizzi, leader of the Materials Software and Data Group at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI, who led the study. (Image: Paul Scherrer Insitute / Giovanni Pizzi) |

Abstract

Density-functional theory methods and codes adopting periodic boundary conditions are extensively used in condensed matter physics and materials science research. In 2016, their precision (how well properties computed with different codes agree among each other) was systematically assessed on elemental crystals: a first crucial step to evaluate the reliability of such computations. In this Expert Recommendation, we discuss recommendations for verification studies aiming at further testing precision and transferability of density-functional-theory computational approaches and codes. We illustrate such recommendations using a greatly expanded protocol covering the whole periodic table from Z = 1 to 96 and characterizing 10 prototypical cubic compounds for each element: four unaries and six oxides, spanning a wide range of coordination numbers and oxidation states. The primary outcome is a reference dataset of 960 equations of state cross-checked between two all-electron codes, then used to verify and improve nine pseudopotential-based approaches. Finally, we discuss the extent to which the current results for total energies can be reused for different goals.

Permanent link to this article: https://dannyvanpoucke.be/paper-aiidaconsortium2023-en/

Nov 26 2023

Materiomics Chronicles: week 9 & 10

With the end of the first quarter in week eight, the nine and tenth week of the academic year were centered around the first batch of exams for the first master students of our materiomics program at UHasselt. For the other students in the second master and bachelor, academic life continued with classes.

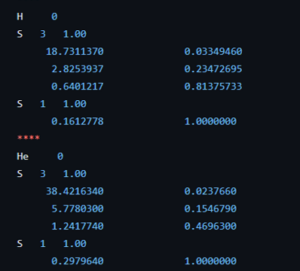

Coefficients of the 63-1G basis set for the H and He atom.

The course introduction to quantum chemistry starts to hone in on the first actual fully realistic system: the H atom. But before we get there, the students of the second bachelor chemistry extended their particle on a ring model system to an infinite number of ring systems: i.e. discs, spheres, and balls. Separation of variables has no longer any secrets for them. Now they are ready for reality after many weeks of abstract toy models. The third bachelor students on the other hand had their first ever contact with real practical quantum chemistry (i.e. computational chemistry) during the course quantum and computational chemistry. They learned about Hartree-Fock, the self-consistent field method, basis sets and slater orbitals. They entered this new world with a practical exercise class where, using jupyter notebooks and the psi4 package, they performed their first even quantum chemical calculations. Starting with the trivial H and He atom systems as a start, since for these we have calculated exact solutions during the classes of this course. This way, we learned about the quality of different basis sets and the time of calculations.

In the master materiomics, the first master students had their exams on Fundamentals of materials modeling, and Properties of functional materials, where all showed they understood the topics presented to sufficient degree making them ready for the second quarter. For the second master students, the course on Density Functional Theory held a lecture on the limitations of DFT and a guest lecture on conceptual DFT.

With week 10 drawing to a close, we added another 15h of classes, ~1h of video lecture and 2h of guest lectures, putting our semester total at 106h of live lectures. Upwards and onward to weeks 11 & 12.

Permanent link to this article: https://dannyvanpoucke.be/materiomics-chronicles-week-9-10/

Nov 05 2023

Materiomics Chronicles: week 7

After a relatively chill week six, the seventh week of the academic year ended up being complicated. As it was fall-break the week only consisted of two class days at university. However, primary schools are closed entirely so our son was at home having a holiday, while both parents were trying to juggle classes and project proposal deadlines as well as additional administrative reporting. A second evaluation meeting with the students of our materiomics program at UHasselt took place (second master this time), and also these students appreciated the effort put into creating their classes.

Although there were only two days of teaching, this did not mean there was little work there. The students of the second bachelor in chemistry extended their knowledge of a particle in a box to the model of a particle on a ring, during the course introduction to quantum chemistry. Similar as for a particle in a box, this can be considered a simplified model for a circular molecule like benzene, allowing us to estimate the first excitation quite accurately.

For the course Fundamentals of Materials Modeling, there was a lecture introducing the first master students materiomics into the very basics of machine learning, as well as an exercise session. During these, the students learned about linear regression, decision trees and support vector machines. This class was also open to students of the bachelor programs to get a bit of an idea of the content of the materiomics program. Finally, the first master students also presented the results of their lab on finite element modeling as part of the course Fundamentals of Materials Modeling. They presented flow studies around arrows, reef and car models, as well as heat transfer in complex partially insulated systems, as well as sinking boats. They showed they clearly gained insight through this type of hands-on tasks, which is always a joy to note, resulting in grades reflecting their efforts and insights.

Though this week was rather short, we added another 6h of classes, putting our semester total at 91h of live lectures. Upwards and onward to week 8.

Permanent link to this article: https://dannyvanpoucke.be/materiomics-chronicles-week-7/

Oct 29 2023

Materiomics Chronicles: week 6

After surviving week five, the sixth week of the academic year feels almost relaxing. However, all the effort is worth it, and I was happy to hear the students of our materiomics program at UHasselt appreciate the effort put into creating their classes, during an evaluation meeting.

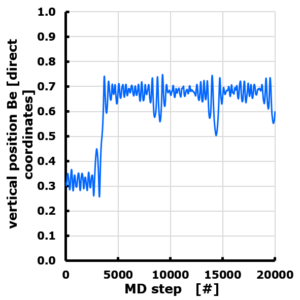

The evolution of the Z position of a Be atom on Graphene. Periodic cell with 10 Angstrom vacuum along z direction. Z position is given in direct coordinates (0…1), with the graphene sheet positioned at z=0 (=1). The Be atom is van der Waals bonded, and moves through the vacuum to attach to the “bottom” side of the sheet, though originally positioned at the “top” side.

Though the week was not as intense as the week before does not mean there were no classes at all. The second bachelor students in chemistry continued their studies of particles in simple potentials though the study of a particle in a square infinite potential well during the course introduction to quantum chemistry. During the course quantum and computational chemistry, the third bachelor chemistry, the He atom was now studied by means of the variational method, introducing the concepts of effective nuclear charge and shielding in a natural way.

While the bachelor students could take a backseat approach during the lectures (except for calculating some bbracket integrals), the master materiomics students had to do most of the heavy lifting during their classes. For the course on Density Functional Theory there was response lecture as well as a lab-session where they studied the dynamics of Be on and around graphene, while the first master students had their second presentation & discussion session on the computational aspects of the papers studied in the course Properties of functional materials.

At the end of this week, we added another 11h of live classes and ~2h of video lectures, putting our semester total at 85h of live lectures. Upwards and onward to week 7.

Permanent link to this article: https://dannyvanpoucke.be/materiomics-chronicles-week-6/

Oct 22 2023

Materiomics Chronicles: week 5

After week four, this fifth week of the academic year is most arguably the most intense and hectic week of teaching. With 22h of classes and still two classes that needed to be prepared from scratch (even including weekends time was running out), I’m tired but happy it is over. However, all the effort is worth it, and I was happy to hear the students of our materiomics program at UHasselt appreciate the effort put into creating their classes, during an evaluation meeting.

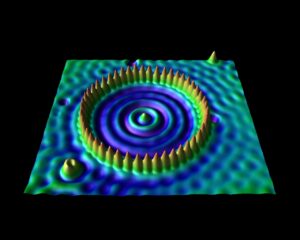

The corral is an artificial structure created from 48 iron atoms (the sharp peaks) on a copper surface. The wave patterns in this scanning tunneling microscope image are formed by copper electrons confined by the iron atoms. Don Eigler and colleagues created this structure in 1993 by using the tip of a low-temperature scanning tunneling microscope (STM) to position iron atoms on a copper surface, creating an electron-trapping barrier. This was the first successful attempt at manipulating individual atoms and led to the development of new techniques for nanoscale construction.

source: https://www.nisenet.org/catalog/scientific-image-quantum-corral-top-view

For the second bachelor students in chemistry the introduction to quantum chemistry finally put them into contact with some “real” quantum mechanics when they were introduced into the world of potential barriers, steps, and wells. Though these are still abstract and toy-model in nature, they provide a first connection with reality, where they can be seen as crude approximations of the potential experienced by valence electrons near the surface, or STM experiments. They were also introduced to my favorite quantum system related to this course: the quantum corral. Without any effort it can be used in half a dozen situations with varying complexity to show and learn basic quantum mechanics. For the third bachelor chemistry students the course quantum and computational chemistry finally provided them the long promised first example of a non-trivial quantum chemical object: The Helium atom. With it’s two electrons, we break free of the H-atom(-like) world. Using perturbation theory and Slater determinant wave functions, we made our first approximations of its energy. In addition, these students also had a seminar for their course Introductory lectures in preparation to the bachelor project (Kennismakingstraject m.b.t. stage en eindproject, in Dutch). During this lecture I gave a brief introduction and overview of the work I did in the past and the work we do in our research group QuATOMs, which although “quantum” is quite different of what the students experience during their courses on quantum chemistry.

In the materiomics program, the first master students continued their travels into the basics of force-fields during the lecture of the course Fundamentals of materials modelling. The exercise class of this week upped the ante by moving from ASE to LAMMPS for practical modeling of alkane chains, which was also the topic of their second lab session. In the course Properties of functional materials, we investigated the ab initio modelling of vibrations. During the exercise classes we investigated precalculated phonon spectra in the materials-project database, as well as calculated our own vibrational spectrum at the gamma-point of the first Brillouin zone. During the second master course Machine learning and artificial intelligence in modern materials science the central theme was GIGO (Garbage-In-Garbage-Out). How can we make sure our data is suitable and good enough for our models to return useful results. We therefore looked into data-preparation & cleaning, as well as clustering methods.

At the end of this week, we have added another 22h of live lectures and ~1h of video lectures, putting our semester total at 74h of live lectures. Upwards and onward to week 6.

Permanent link to this article: https://dannyvanpoucke.be/materiomics-chronicles-week-5/

Oct 15 2023

Materiomics Chronicles: week 4

Week four of the academic year at the chemistry and materiomics programs of UHasselt, we are stepping up the pace a bit…at least for me. The students continue to dive deeper into the various subjects furthering their knowledge gained in the previous weeks.

In the bachelor chemistry program, the third bachelor chemistry extended their knowledge of variational theory to excited states, in the course quantum and computational chemistry. They also saw some first glimpses of the mathematical setup which makes the use of computational methods so important and powerful in quantum chemistry. Finally they proved the Hellmann-Feynman Theorem which makes structure optimization in quantum chemistry practically feasible. For the second bachelor chemistry, the course introduction to quantum chemistry was focused on the time-dependent Schrödinger equation and the uncertainty principle.

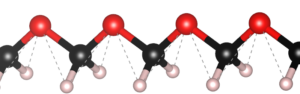

In the first master materiomics, I was the main player this week (and will also be so next week) teaching the classes of two of the three courses. In the course Properties of functional materials, the second module started, which is centered on the computational (quantum mechanical) modeling of materials properties. Here the students build on their recently acquired expertise in DFT to gain further insights into electronic structure calculations both in theory and in practice. In addition, the students also had their first seminar presentation where they present their understanding after studying two papers within the context of the concepts presented during the first module of the course. In the course Fundamentals of materials modelling, we moved to a new level of modeling: atomistic modeling using force-fields. The freshly gained knowledge was also here directly applied through the modeling of bulk aluminum using the ASE library in a jupyter notebook. (For many a first contact with python.) Finally, the students of the second master learned about “dynamical” modeling, in the course on Density Functional Theory, covering NEB calculations for energy barriers as well as basic molecular dynamics (with examples such as the water molecule below).

At the end of this week, we have added another 17h of live lectures and ~1h of video lectures, putting our semester total at 52h of live lectures. Upwards and onward to week 5.

Permanent link to this article: https://dannyvanpoucke.be/materiomics-chronicles-week-4/

Oct 07 2023

Materiomics Chronicles: week 3

In week three of the academic year at the chemistry and materiomics programs of UHasselt, the students started to put their freshly gained new knowledge of weeks 1 and 2 into practice with a number of exercise classes.

For the second bachelor chemistry students, this meant performing their first calculations within the context of the course introduction to quantum chemistry. At this point this is still very mathematical (e.g., calculating commutators) and abstract (e.g., normalizing a wave function or calculating the probability of finding a particle, given a simple wave function), but this will change, and chemical/physical meaning will slowly be introduced into the mathematical formalism. For the third bachelor chemistry, the course quantum and computational chemistry continued with perturbation theory, and we started with the variational method as well. The latter was introduced through the example of the H atom, for which the exact variational ground state was recovered starting from a well chosen trial wave function.

Ball-and-stick representation of an infinite polymethylene glycol (POM) chain.

In the master materiomics, the first master course fundamentals of materials modelling, dove into the details underpinning DFT introducing concepts like pseudo-potentials, the frozen-core approximation, periodic boundary conditions etc. This knowledge was then put into practice during a second exercise session working on the supercomputer, as a last preparation for the practical lab exercise the following day. During this lab, the students used the supercomputer to calculate the Young modulus of two infinite linear polymers. An intense practical session which they all executed with great courage (remember 2 weeks ago they never heard of DFT, nor had they accessed a supercomputer). Their report for this practical will be part of their grade.

For the second master materiomics, the course focused on Density Functional Theory consisted of a discussion lecture, covering the topics the students studied during their self study assignments. In addition, I recorded two video lectures for the blended learning part of the course. For the course Machine learning and artificial intelligence in modern materials science self study topics were covered in such a discussion lecture as well. In addition, the QM9 data set was investigated during an exercise session, as preparation for further detailed study.

At the end of this week, we have added another 16h of live lectures and ~1h of video lectures, putting our semester total at 35h of live lectures. Upwards and onward to week 4.

Permanent link to this article: https://dannyvanpoucke.be/materiomics-chronicles-week-3/

Sep 24 2023

Materiomics Chronicles: week 1

The first week of the academic year at UHasselt has come to an end, while colleagues at UGent and KULeuven are still preparing for the start of their academic year next week. Good luck to all of you.

This week started full throttle for me, with classes for each of my six courses. After introductions in classes with new students (for me) in the second bachelor chemistry and first master materiomics, and a general overview in the different courses, we quickly dove into the subject at hand.

The second bachelor students (introduction to quantum chemistry) got a soft introduction into (some of) the historical events leading up to the birth of quantum mechanics such as the black body radiation, the atomic model and the nature of light. They encountered the duck-rabbit of particle-wave duality and awakened their basic math skills with the standing wave problem. For the third bachelor students, the course on quantum and computational chemistry started with a quick recap of the course introduction to quantum mechanics, making sure they are all again up to speed with concepts like braket-notation and commutator relations.

For the master materiomics it was also a busy week. We kicked of the 1st Ma course Fundamentals of materials modeling, which starts of calm and easy with a general picture of the role of computational research as third research paradigm. We discussed in which fields computational research can be found (flabbergasting students with an example in Theology: a collaboration between Sylvia Wenmackers & Helen De Cruz), approximation vs idealization, examples of materials research at different scales, etc. As a homework assignment the students were introduced into the world of algorithms through the lecture of Hannah Fry (Should computers run the world). For the 2nd Ma, the courses on Density Functional Theory and Machine learning and artificial intelligence in modern materials science both started. The lecture of the former focused on the nuclear wave function and how we (don’t) deal with it in DFT, but still succeed in optimizing structures. During the lecture on AI we dove into the topics of regularization and learning curves, and extended on different types of ensemble models.

At the end of week 1, this brings me to a total of 12h of lectures. Upwards and onward to week 2.

Permanent link to this article: https://dannyvanpoucke.be/materiomics-chronicles-week-1/