This year I participated in the Robbert Dijkgraaf essay-contest 2015.

The central theme of the contest was imagination, and in my contribution

I presented the role of imagination in computational materials science,

and why it is so important for this field.

The original Dutch version of the essay can be found here.

Imagine a world where you can actually see atoms. Even more, you can use them as LEGOs and manipulate them to do your bidding. Imagine a world in which you can switch off the laws of nature, or create new ones which are more to your liking. In such a world, you are in charge. Welcome to my world: the world of “computational materials science“.

It would be a nice start for a commercial for this research field. The accompanying clip would then show images fading into one another of supercomputers and animations of chemical and biochemical processes at the atomic scale. Moving in a fast-forward pace into our future with science-fiction-like orbital labs where calculated materials are immediately transformed into new medicine, ultra-thin screens and applications for the aerospace industry.  The ever faster flood of images culminates in the final slogan:”Simulate the future” with a subtext urging you to go study computational materials science. I assume that such a clip would tempt peoples imagination. It addresses our human urge to create, and holds the promise that you can do anything you want, as long as you can imagine it. In fact, your imagination becomes the only limiting factor.

The ever faster flood of images culminates in the final slogan:”Simulate the future” with a subtext urging you to go study computational materials science. I assume that such a clip would tempt peoples imagination. It addresses our human urge to create, and holds the promise that you can do anything you want, as long as you can imagine it. In fact, your imagination becomes the only limiting factor.

As with most commercial, this one also presents reality slightly more beautiful than it actually is. As for any other scientist in any other field, your contribution to progress as a computational materials scientist is rather more limited than you would like it to be. This is a normal aspect of science. The presented divine omnipotence and omniscience, on the other had, are attainable. As a computational scientist you do have absolute control over the atomic positions and the forces at play. In contrast, an experimental scientist is forced to deal with the quirks of nature and his or her machinery. This omnipotence allows you to create any world you can imagine…inside a computer.

As a scientist, you wish to understand the world around you. This limits the freedom you gained through your omnipotence, unless you would choose to join a team of game-designers. It, however, does not mean that your creativity is curtailed in any way. On the contrary. Where the team of game-designers knows the entire story to be told, including rules and laws of nature relevant for the game world, this is not the case for computational materials science. For the latter it is often their quest to discover the story-line as they go, including relevant laws of nature. As a computational materials scientist, you become the narrator, whose task consist of thinking up new stories time and time again. The narrator, who needs to tweak existing plots, extending or confining story-lines, until the final story fits the shape of reality.

Luckily, you are not alone to bring this daunting task to a successful end. You always have the support of your loyal sidekick: your supercomputer. Using its brute force, your sidekick calculates the effects of any intrigue or plot twist you can imagine. Based on your introductory chapter, in which you describe the world and its natural laws, it will allow the story to unfold. By asking him the right questions, and comparing his answers to reality, you learn which parts of your story don’t really fit reality yet.

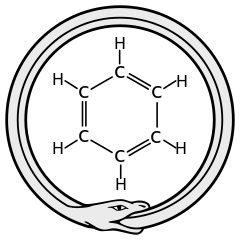

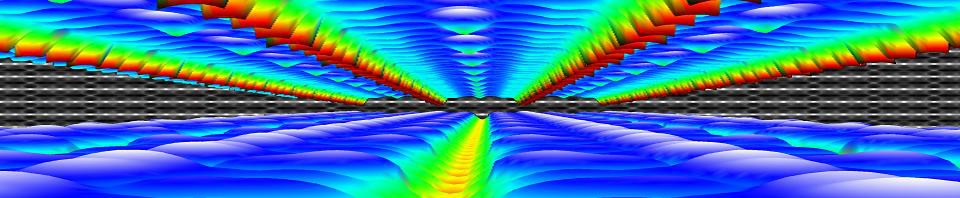

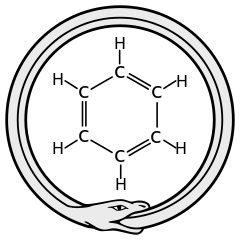

How you should rewrite your introductory chapter differs every time. Sometimes it is clear what is going on: an essential character is missing (e.g. an impurity atom which is distorting the crystal lattice), or the character lives at the wrong location (not site A, then let us see about site B?). It becomes more difficult when a character refuses to play the role it was dealt (e.g. Pt atoms that remain invisible for STM, so who is going to play the role of the nanowire we observe?). The most difficult situation occurs with the need for a full rewrite of the introductory chapter. This provides too much freedom, since it is our knowledge of the limitations of reality which provides the necessary support and guidance for drafting the story-line. In such a case, you need an inspiring idea which provides you with a new point of view. Inspiration can come in many forms and at any time, often when least expected. A well-known example is this of the theoretical chemist Kekulé who, in a daydream, saw a snake bite its own tail. As a result Kekulé was able to envision the ring-shape of the benzene molecule. Such wonderful problem solving twists-of-mind are rare. They are often the consequence of long and intense study of a single problem, which drive you to the limit, since they require you to imagine something you have never thought of before. In management-circles this is called “thinking-outside-the-box”, which sound a lot easier than it actually is. It does not mean that all of the sudden everything goes, you always have to bear in mind the actual box you started from.

How you should rewrite your introductory chapter differs every time. Sometimes it is clear what is going on: an essential character is missing (e.g. an impurity atom which is distorting the crystal lattice), or the character lives at the wrong location (not site A, then let us see about site B?). It becomes more difficult when a character refuses to play the role it was dealt (e.g. Pt atoms that remain invisible for STM, so who is going to play the role of the nanowire we observe?). The most difficult situation occurs with the need for a full rewrite of the introductory chapter. This provides too much freedom, since it is our knowledge of the limitations of reality which provides the necessary support and guidance for drafting the story-line. In such a case, you need an inspiring idea which provides you with a new point of view. Inspiration can come in many forms and at any time, often when least expected. A well-known example is this of the theoretical chemist Kekulé who, in a daydream, saw a snake bite its own tail. As a result Kekulé was able to envision the ring-shape of the benzene molecule. Such wonderful problem solving twists-of-mind are rare. They are often the consequence of long and intense study of a single problem, which drive you to the limit, since they require you to imagine something you have never thought of before. In management-circles this is called “thinking-outside-the-box”, which sound a lot easier than it actually is. It does not mean that all of the sudden everything goes, you always have to bear in mind the actual box you started from.

As a computational materials scientist you have to combine your omnipotence over your virtual world with your power to imagine new worlds, hoping to see a glimmer of reality in the reflections of your silicon chips.

The ever faster flood of images culminates in the final slogan:”Simulate the future” with a subtext urging you to go study computational materials science. I assume that such a clip would tempt peoples imagination. It addresses our human urge to create, and holds the promise that you can do anything you want, as long as you can imagine it. In fact, your imagination becomes the only limiting factor.

The ever faster flood of images culminates in the final slogan:”Simulate the future” with a subtext urging you to go study computational materials science. I assume that such a clip would tempt peoples imagination. It addresses our human urge to create, and holds the promise that you can do anything you want, as long as you can imagine it. In fact, your imagination becomes the only limiting factor. How you should rewrite your introductory chapter differs every time. Sometimes it is clear what is going on: an essential character is missing (e.g. an

How you should rewrite your introductory chapter differs every time. Sometimes it is clear what is going on: an essential character is missing (e.g. an