Zeolites and Metal-Organic Frameworks

Some good new news: The book on zeolites and porous frameworks for which I wrote a chapter on modeling with Bartlomiej Szyja has become open access and can be found here.

Jan 01 2018

2017 has come and gone. 2018 eagerly awaits getting acquainted. But first we look back one last time, trying to turn this into a old tradition. What have I done during the last year of some academic merit.

Publications: +4

Completed refereeing tasks: +8

Conferences & workshops: +5 (Attended)

PhD-students: +1

Bachelor-students: +2

Current size of HIVE:

Hive-STM program:

Jan 01 2017

2016 has come and gone. 2017 eagerly awaits getting acquainted. But first we look back one last time, trying to turn this into a tradition. What have I done during the last year of some academic merit.

Publications: +4

Completed refereeing tasks: +5

Conferences: +4 (Attended) & + 1 (Organized)

PhD-students: +2

Current size of HIVE:

Hive-STM program:

Jan 01 2016

With 2015 having past on moving quickly toward oblivion, and 2016 freshly knocking at our door, it is time to look back and contemplate what we have done over the course of the previous year.

Publications: +5

Journal covers:+1

Completed refereeing tasks: +11

Conferences: +3 (Attended) & + 1 (Organized)

Master-students: +1

Jury member of PhD-thesis committee: +1

Current size of HIVE:

Hive-STM program:

Mar 19 2015

It could be that I’ve perhaps found out a little bit about the structure

of atoms. You must not tell anyone anything about it. . .

–Niels Bohr (1885 – 1965),

in a letter to his brother (1912)

Getting the news that a paper got accepted for publication is exciting news, but it can also be a little bit sad since it indicates the end of a project. Little over a month ago we got this great news regarding our paper for the journal of chemical information and modeling. It was the culmination of a side project Goedele Roos and I had been working on, in an on-and-off fashion, over the last two years.

When we started the project each of us had his/her own goal in mind. In my case, it was my interest in showing that my Hirshfeld-I code could handle systems which are huge from the quantum mechanical calculation point of view. Goedele, on the other hand, was interested to see how good Hirshfeld-I charges behaved with increasing size of a molecular fraction. This is of interest for multiscale modeling approaches, for which Martin Karplus, Michael Levitt, and Arieh Warshel got the Nobel prize in chemistry in 2013. In such an approach, a large system, for example a solvated biomolecule containing tens of thousands of atoms, is split into several regions. The smallest central region, containing the part of the molecule one is interested in is studied quantum mechanically, and generally contains a few dozen up to a few hundred atoms. The second shell is much larger, and is described by force-field approaches (i.e. Newtonian mechanics) and can contain ten of thousands of atoms. Even further from the quantum mechanically treated core a third region is described by continuum models.

What about the behavior of the charges? In a quantum mechanical approach, even though we still speak of electrons as-if referring to classical objects, we cannot point to a specific point in space to indicate: “There it is”. We only have a probability distribution in space indicating where the electron may be. As such, it also becomes hard to pinpoint an atom, and in an absolute sense measure/calculate it’s charge. However, because such concepts are so much more intuitive, many chemists and physicists have developed methods, with varying success, to split the electron probability distribution into atoms again. When applying such a scheme on the probability distributions of fractions of a large biomolecule, we would like the atoms at the center not to change to much when the fraction is made larger (i.e. contain more atoms). This would indicate that from some point onward you have included all atoms that interact with the central atoms. I think, you can already see the parallel with the multiscale modeling approach mentioned above; where that point would indicate the boundary between the quantum mechanical and the Newtonian shell.

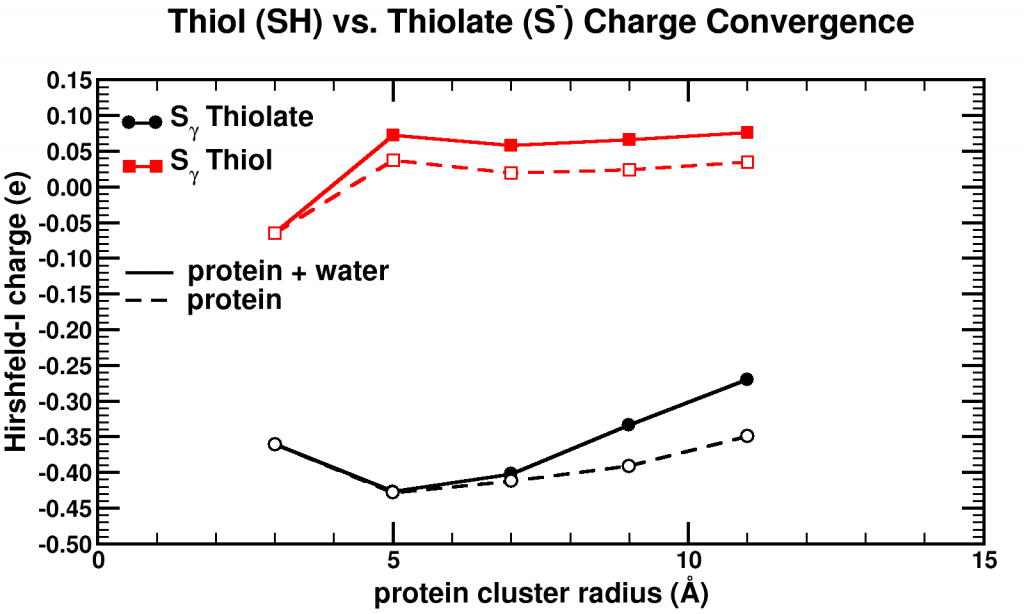

Convergence of Hirshfeld-I charges for clusters of varying size of a biomolecule. The black curves show the charge convergence of an active S atom, while the red curves indicate a deactivated S atom.

Although, we expected to merely be studying this convergence behavior, for the particular partitioning scheme I had implemented, we dug up an unexpected treasure. Of the set of central atoms we were interested all except one showed the nice (and boring) convergence behavior. The exception (a sulfur atom) showed a clear lack of convergence, it didn’t even show any intend toward convergence behavior even for our system containing almost 1000 atoms. However, unlike the other atoms we were checking, this S atom had a special role in the biomolecule: it was an active site, i.e. the atom where chemical reactions of the biomolecule with whatever else of molecule/atom are expected to occur.

Because this S atom had a formal charge of -1, we bound a H atom to it, and investigated this set of new fractions. In this case, the S atom, with the H atom bound to it, was no longer an active site. Lo and behold, the S atom shows perfect convergence like all other atoms of the central cluster. This shows us that an active site is more than an atom sitting at the right place at the right time. It is an atom which is reaching out to the world, interacting with other atoms over a very long range, drawing them in (>10 ångström=1 nm is very far on the atomic scale, imagine it like being able to touch someone who is standing >20 m away from you). Unfortunately, this is rather bad news for multiscale modeling, since this means that if you want to describe such an active site accurately you will need an extremely large central quantum mechanical region. When the active site is deactivated, on the other hand, a radius of ~0.5 nm around the deactivated site is already sufficient.

Similar to Bohr, I have the feeling that “It could be that I’ve perhaps found out a little bit about the structure

of atoms.”, and it makes me happy.

Feb 21 2015

(source via Geographical Perspectives)

The last three months have been largely dedicated to the review of publications: On the one hand, some of my own work was going through the review-process, while on the other hand, I myself had to review several publications for various journals. During this time I got to see the review reports of fellow reviewers, both for my own work and the work I had to reviewed. Because the peer-review experience is an integral part of modern science, some hints for both authors and reviewers:

When you get your first request to review a paper for a peer reviewed journal‡, this is an exciting experience. It implies you are being recognized by the community as a scientist with some merit. However, as time goes by, you will see the number of these requests increase, and your available time decreases (this is a law of nature). As such, don’t be too eager to press that accept button. If you do not have time to do it this week, chances are slim you will have time next week or the week after that. Only accept when you have time to do it NOW. This ensures that you can provide a qualitative report on the paper under review (cf. point below) No-one will be angry if you say no once in a while. Some journals also ask if you can suggest alternate reviewers in such a case. As a group group leader (or more senior scientist) this is a good opportunity to introduce more junior scientists into the review process.

‡ Not to be mistaken with predatory journals, presenting all kinds of schemes in which you pay heavily for your publication to get published.

You have always been selected specifically for your qualities, which in some cases means your name came up in a google search combining relevant keywords (not only authors and reviewers are victims of the current publish-or-perish mentality). Don’t be afraid to decline if a paper is outside your scope of interest/understanding. In my own case, I quite often get the request to review experimental papers which I will generally decline, unless I the abstract catches my interest. In such a case, it is best to let the editor know via a private note that although you provide a detailed report, you expect there to be an actual specialist (in my case an experimentalist) present with the other reviewers which can judge the specialized experimental aspects of the work you are reviewing.

In some fields it is normal for the review process to be double blind (authors do not know the reviewers, and the reviewers do not know the authors), in others this is not the case. However, to be able to review a paper on it’s merit try to ignore who the authors are, it should reduce bias (both favorable or unfavorable), because that is the idea of science and writing papers: it should be about the work/science not the people who did the science.

Single sentence reviews stating how good/bad a paper is, only shows you barely looked at it (this may be due to time constraints or being outside your scope of expertise: cf. above). Although it may be nice for the authors to hear you found their work great and it should be published immediately, it leaves a bit of a hollow sense. In case of a rejection, on the other hand it will frustrate the authors since they do not learn anything from this report. So how can they ever improve it?

No matter how good paper, one can always make remarks. Going from typographical/grammatical issues (remember, most authors are not native English speakers) to conceptual issues, aspects which may be unclear. Never be afraid to add these to your report.

Although this is a quite a obvious statement, there appear to be authors who just send in their draft to a high ranking journal to get a review-report and then use this to clean up the draft and send it elsewhere. When you submit a paper you should always have the intention of having it accepted and published, and not just use the review progress to point out the holes in your current work in progress.

Some people like to make figures and tables, others don’t. If you are one of the latter, whatever you do, avoid making sloppy figures or tables (e.g. incomplete captions, missing or meaningless legends, label your axis, remove artifacts from your graphics software, or even better switch to other graphics software). Tables and figures are capitalized because they are a neat and easy to use means of transferring information from the author to the reader. In the end it is often better not to have a figure/table than to have a bad one.

Although as a species we are called homo sapiens (wise man) in essence we are rather pan narrans (storytelling chimpanzee). We tell stories, and have always told stories, to transfer knowledge from one generation to another. Fairy-tales learn us a dark forest is a dangerous place while proverbs express a truth based on common sens and practical experience.

As such, a good publication is also more than just a cold enumeration of a set of data. You can order you data to have a story-line. This can be significantly different from the order in which you did your work. You could just imagine how you could have obtained the same results in a perfect world (with 20/20 hindsight that is a lot easier) and present steps which have a logical order in that (imaginary) perfect world. This will make it much easier for your reader to get through the entire paper. Note that it is often easier to have a story-line for a short piece of work than a very long paper. However, in the latter case the story-line is even more important, since it will make it easier for your reader to recollect specific aspects of your work, and easily track them down again without the need to go through the entire paper again.

Some journals allow authors to provide SI to their work. This should be data, to my opinion, without which the paper also can be published. Here you can put figures/tables which present data from the publication in a different format/relation. You can also place similar data in the SI: E.g. you have a dozen samples, and you show a spectrum of one sample as a prototype in the paper, while the spectra of the other samples are placed in SI. What you should not do is put part of the work in the SI to save space in the paper. Also, something I have seen happen is so-called combined experimental-theoretical papers, where the theoretical part is 95% located in the SI, only the conclusions of the theoretical part are put in the paper itself. Neither should you do the reverse. In the end you should ask yourself the question: would this paper be published/publishable under the same standards without the information placed in SI. If the answer is yes, then you have placed the right information in the SI.

Since many, if not all, funding organisations and promotion committees use the number of publications as a first measure of merit of a scientist, this leads to a very unhealthy idea that more publications means better science. Where the big names of 50 years ago could actually manage to have their first publication as a second year post doc, current day researchers (in science and engineering) will generally not even get their PhD without at least a handful publications. The economic notion of ever increasing profits (which is a great idea, as we know since the economic crisis of 2008) unfortunately also transpires in science, where the number of publications is the measure of profit. This sometimes drives scientists to consider publishing “Least Publishable Units”. Although it is true that it is easier to have a story-line for a short piece of work, you also loose the bigger picture. If you consider splitting your work in separate pieces, consider carefully why you do this. Should you do this? Fear that a paper will be too long is a poor excuse, since you can structure your work. Is there actually anything to gain scientifically from this, except one additional publication? Funding agencies claim to want only excellent work; so remind them that excellent work is not measured in simple accounting numbers.

Disclaimer: These hints reflect my personal opinion/preferences and as such might differ from the opinion/preference of your supervisor/colleagues/…, but I hope they can provide you an initial guide in your own relation to the peer-review process.