The last three days of the conference, the virtual materials design session took place. This session was specifically focused on computational materials design. Because of this focus, the attendance was rather low, mainly computational materials scientists. Apparently, this type of specialized focus on computational work is the best way not to reach the general experimental public in the same field. As a computational scientist the only way to circumvent this, is by applying for a presentation in a relevant experimental session. This requires you to make a less technical presentation, but this is not a bad thing, since it forces you to think about your results and understand them in more simple terms.

An example of such a presentation was given Dr. Ong who discussed his high-throughput ab initio setup for designing solid state electrolytes. He showed that a material (Li10GeP2S12) which was thought to be a 1D conductor, actually is a 3D conductor, however, the Li-conductivity in the directions perpendicular to the 1D direction is ~100 times smaller, explaining why they were not noticed before. He also presented newly predicted materials for Li-transport, which lead to a standard experimental remark that such computational predictions mean very little, since they do not take into account temperature, and as such these structures may not be stable. Although such remarks are “in theory” true, and are a nice example of a lack of understanding outside the computational community, in this case, the material the experimental researcher was referring to was recently synthesized and found to be stable.

On Thursday morning, I had the opportunity to present my contributed presentation. In contrast to my invited presentation, this presentation was solely focused on doped cerium dioxide. Using a three-step approach, we investigated all different contributions of the dopants to their modification of the mechanical properties of CeO2. In the first step, we look at group IV dopants, since Ce has an oxidation state of +IV in CeO2. Here we show that the character of the valence electrons (p or d) plays an important role with regard to stability and mechanical properties. In our second step dopants with an oxidation state different from +IV are considered, without the presence of oxygen vacancies. In this case, the same trends and behavior is observed as in the first step. In the third and last step also oxygen vacancies are included. We show that oxygen vacancies have a stabilizing influence of the doped system. Furthermore, the oxygen vacancies make CeO2 mechanically softer, i.e. reducing the bulk modulus.

In the afternoon, Prof. Frederico Rosei, of NanoFemto lab in Canada, gave an entertaining lecture on “Mentorship for young scientists: Developing scientific survival skills”. It presented an interesting forum to find out that, as scientists, we all seem to struggle with the same things. We want to do what we like (research), and invest a lot in this, unfortunately external forces (the struggle for funding/job security) complicate life. Frederico centered his lecture around three points of importance/goals a young scientist should always try to be aware of:

- Know yourself

- Plan ahead

- Find a mentor

Although these are lofty goals, they tend to be quite none-trivial in the current-day scientific environment. Finding a mentor, i.e. a senior scientist with time on his/her hands not involved in your projects, is a bit like looking for a unicorn. Unlike the unicorn, they do exist, but there are very very few of them (How many professors do you know with spare time?). Planning ahead, and following your own plans are nice in theory, unfortunately a young scientists’ life (i.e. everyone below tenured professorship) tends to be ruled by funding in a kind of life or dead setup. I am not saying this is not the case for tenured professors, however, it is not their own life and death. For all other scientist : No funding=no job=end scientific career. As such, the pressure to publish (yes, funding agencies only count your papers, not how good/bad they are even though that is the official statement) is high, and will have a detrimental influence on the quality of science and of what is being published (if it isn’t already the case). I truly wished, the world could be as Prof. Rosei envisions it. Back to more happy subjects.

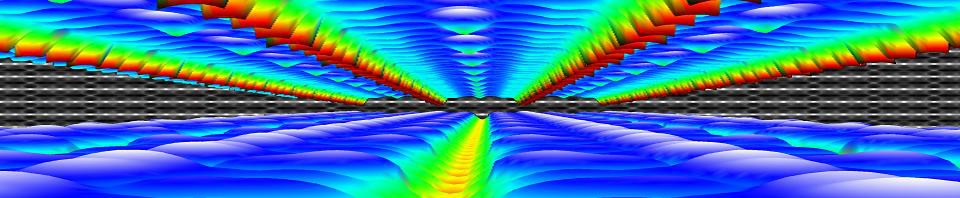

Friday was the last day of the conference. In the morning I again attended the virtual materials design session, but as with all other sessions several presentations were canceled, apparently snow is wreaking some havoc in New York airport, preventing several presenters not to be able to make it. Luckily Eva Zarkadoula made it to the conference to present her very nice modeling work: “Molecular Dynamic Simulations of Synergistic Effects in Ion Track Formation”. Using classical molecular dynamics simulations, she simulated how incoming high energy radiation traces a path trough a material allowing one to use this material as a detector. In contrast to what I would have imagined, perfectly crystalline material shows very little damage after the radiation has passed through. Even though initially a clear trace is visible, the system appear to relax back to a more or less perfect crystalline solid upon relaxation, making it a rather poor sensor material. However, if defects are present in the material, the track made by the radiation remains clearly visible. An extremely nice bonus to this work is the fact that direct comparison to experiments is possible.

The conference ended at noon, leaving some time to have a walk on the beach, find some souvenirs, and have a last dinner with colleagues from the conference.